Sniffing Cloud at Cost VNC Sessions

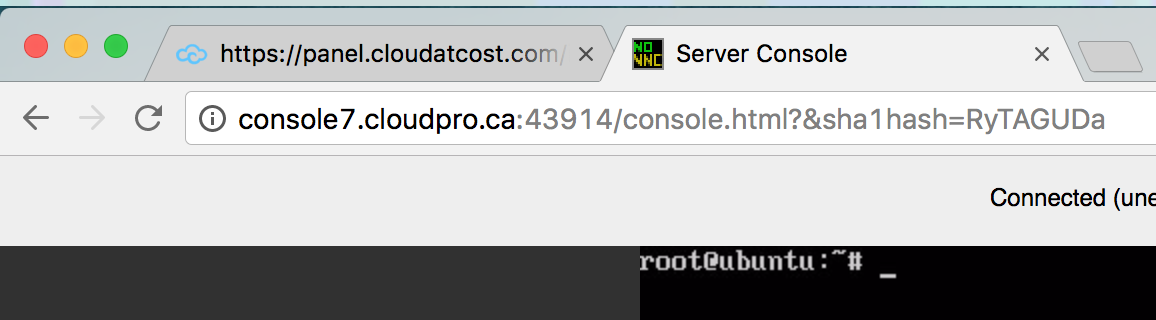

Cloud at Cost is a company that sells virtual resources to a customer for a one-time fee. Users are given an administrative panel where they can create, destroy and gain console access (via VNC) to their virtual machines. Out of curiosity, I decided to do a packet capture of the VNC connection that grants users console access.

Part 1 – Sniffing VNC Connections

When logging into Cloud at Cost, you are brought to the administrative panel. The panel is secured by HTTPS and allows authenticated users to access their virtual machines (this is not abnormal and will be discussed further later in this write-up).

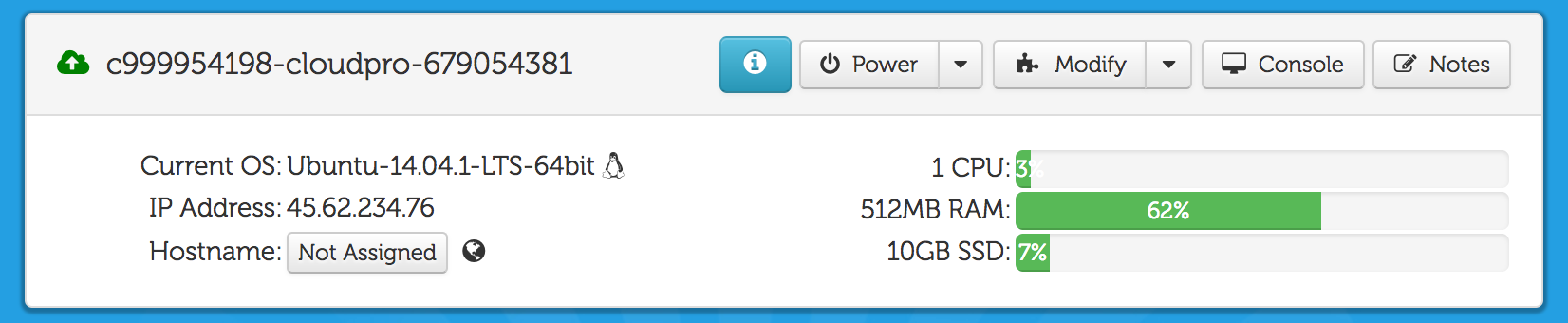

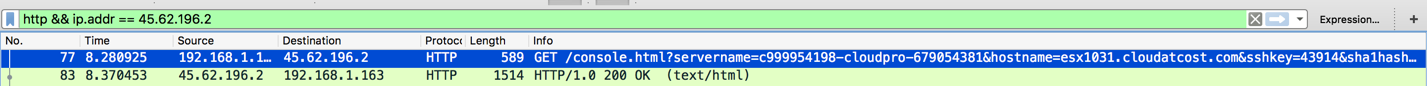

The screenshot above shows how a virtual machine is represented in the administrative panel. Upon clicking “Console,” a request is sent to separate server that initiates the VNC session. That request happens to be a plaintext HTTP GET as shown in the Wireshark capture below:

The full path is:

http://console7.cloudpro.ca:43914/console.html?servername=c999954198-cloudpro-679054381&hostname=esx1031.cloudatcost.com&sshkey=43914&sha1hash=RyTAGUDaRu

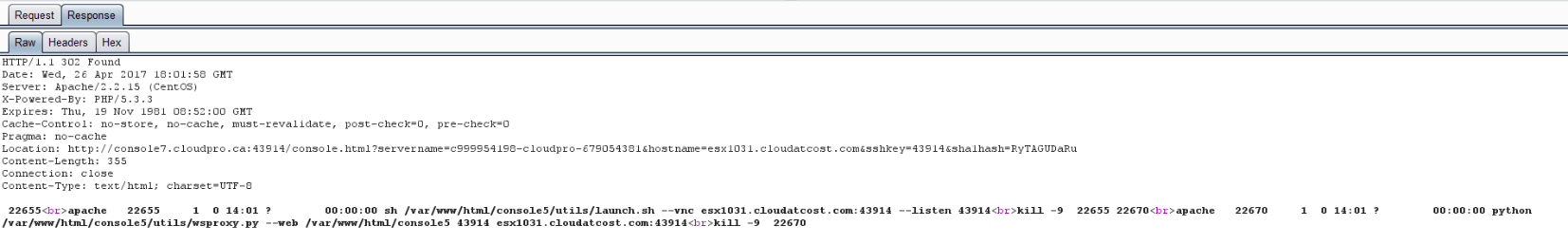

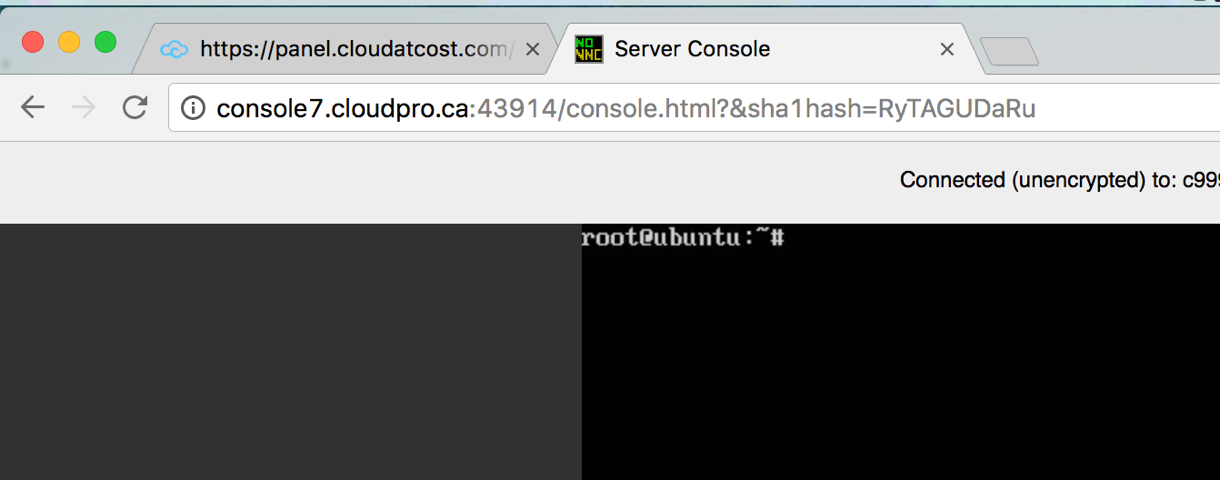

I quickly found the GET parameters had interesting names such as “sshkey.” I was curious to know if the link itself was enough to grant access rather than looking at my authenticated user account at panel.cloudatcost.com. In a private browsing window, I proceeded to access to link manually. Not only was I not prompted to authenticate at all, I was immediately brought to my VM’s VNC session. It would only require a malicious party to intercept HTTP traffic between a user and the Cloud at Cost VNC to gain VNC access to any Cloud at Cost VM. One question that remained was how did my computer determine that specific path? I used Burp to Man-in-the-middle my own connection to panel.cloudatcost.com to try and find where it was referenced. I found it by clicking “Console” it was passed via HTTPS in the “Location” header:

I have not attempted to further analyze the output to see if command injection is possible; however, /var/www/html/console5/utils/wsproxy.py is publicly accessible.

Note: It was discovered that HTTP requests are never sent in subsequent sessions as they are cached indefinitely. I suspect someone intended this as “Security Through Caching.”

Part 2 – Risk of Bruteforcing VNC Sessions

After analyzing numerous connections, it became clear that the URL did not change and by extension did not expire. More specifically, none of the GET parameters expire after a finite amount of time. I began to think, assuming an attacker does not see the initial HTTP request, how practical is it to bruteforce these fields? By comparing the URL with that of other VMs I own, I quickly realized that console7.cloudpro.ca was a common VNC server; however, each VM gets its own unique port number. Given the information thus far we know each VNC connection uses four fields: “servername,” “hostname,” “sshkey,” “sha1hash,” and “port.”

servername=c999954198-cloudpro-679054381 hostname=esx1031.cloudatcost.com sshkey=43914 sha1hash=RyTAGUDaRu port=43914

At first glance, this seems like an unrealistic amount of data to be able to bruteforce. However, you can very quickly see ways to reduce to number of possible permutations. For instance, the sshkey and the port number are the same between requests. Additionally, the sha1hash is 10 characters and contains no numbers or symbols. Probably the biggest reduction of possibilities is that “servername,” “hostname,” and “sshkey” are not actually required to authenticate as you can see below:

What is even more odd is you can remove the last two characters from the sha1hash field and still successfully authenticate:

These new findings reduce the key space down to just a port number and an eight character string of uppercase and lowercase letters. This allows scripted attacks to enumerate all Cloud at Cost VNC Sessions and is significantly more feasible to bruteforce than previously expected with four unique parameters. Just like with the sniffing of the plaintext GET request, once an attacker learned the URL they could simply wait for a user to login—or worse yet—the user might have left a user on their VM logged in thinking to get console access you must first be authenticated with panel.cloudatcost.com.

Part 3 – Leaking Keystrokes

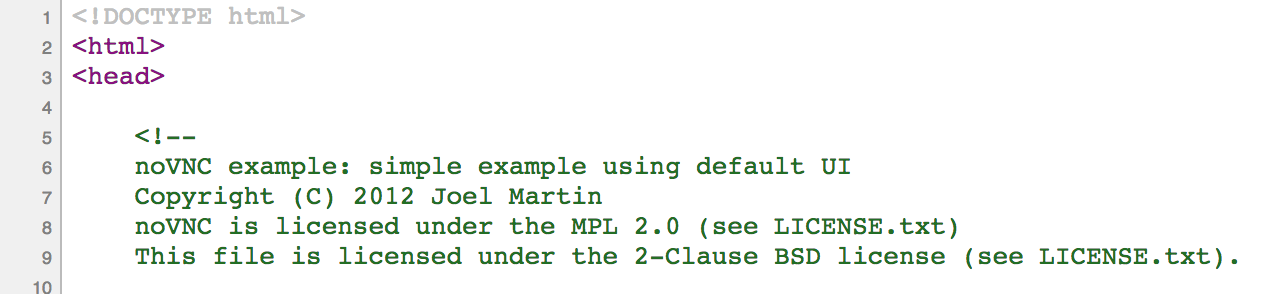

Once the user has successfully connected to the VNC server we see a request to a resource called, “/websockify” followed by TCP data and “Websocket Binary.” While the session is using HTTP, the actual VNC data is encrypted according to the JavaScript files loaded by the webpage. I didn’t know much about what “flavor” of VNC they are using so I attempted to collect information from the server by generating an error. I discovered this can be done by either removing all get parameters or by typing in the incorrect sha1hash value. Once you do this, there will be a red banner displaying an error message. Once an error is generated, if we read the page source, we can view the JavaScript used for the VNC user interface, along with the version of VNC and what files are loaded in.

Once I learned that Cloud at Cost is using noVNC I began to read up on the protocol along with the local JS files that were used for the VNC session. noVNC traditionally runs over the Remote Frame Buffer (RFB) protocol and there are a few important things to understand about the protocol:

- Input Protocol

- Input is sent to the server on each key press

- Protocol Messages

- Uses either a byte stream or is message-based

- Server Response

- Server responds with JPEGs from VNC session

- Protocol Stages

- Handshake

- Initialization Phase

- Normal Protocol Interaction

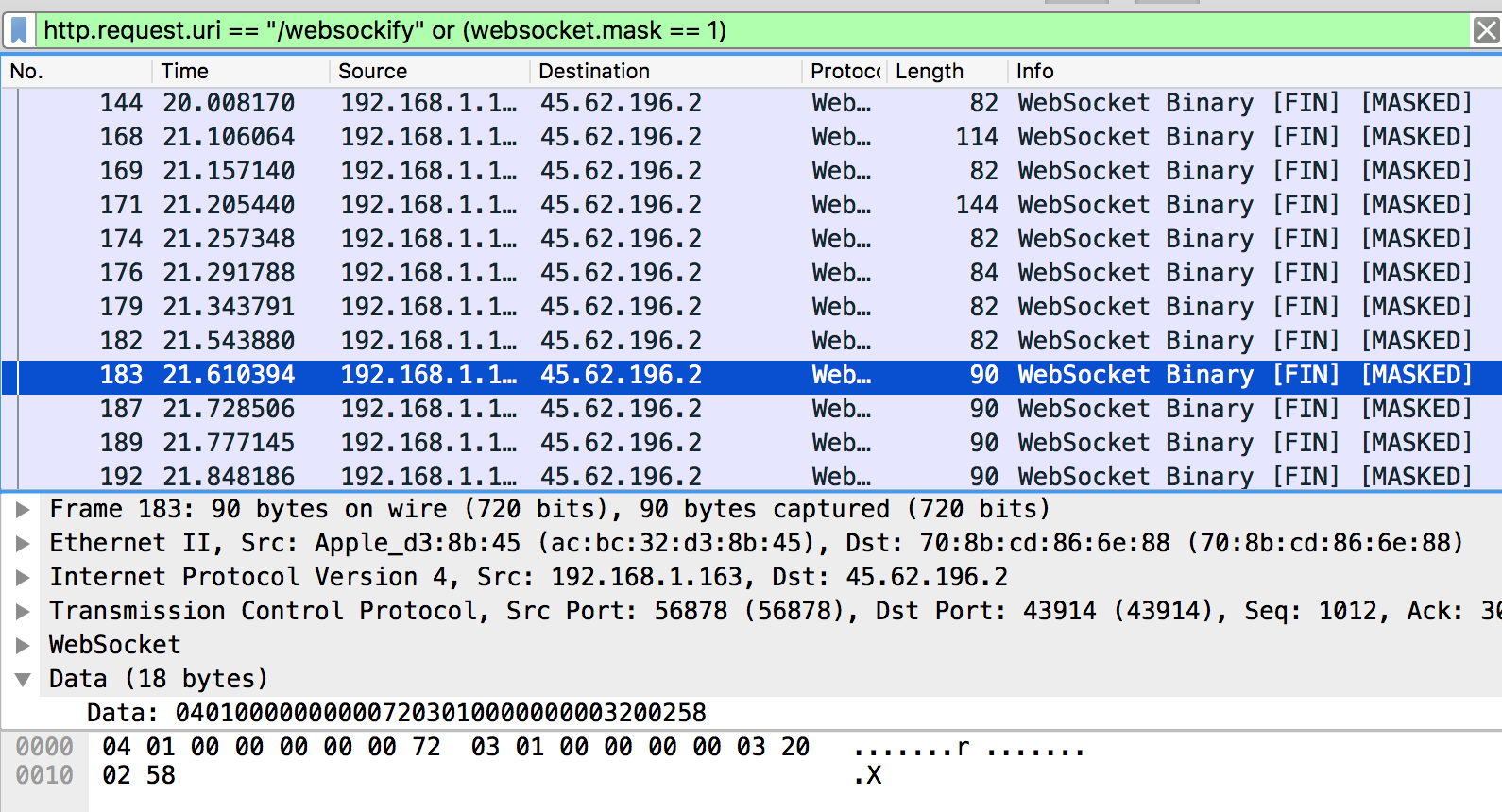

It is at this point I start up a new Wireshark capture and record myself connecting to VNC and then logging into my virtual machine. When reviewing the traffic, I noticed a lot of masked data:

Even though the Websocket stream is encrypted, when viewing only the masked data in Wireshark we see what appears to be a plaintext ‘r’. I then look at the next Websocket packet with the same data only the second hex value changes from “0x01” to “0x00”. I then learn, the two leading hex values “0x04” and “0x01” are representative of a key being pressed down on the keyboard and “0x04” and “0x00” is the key being released. By the third packet, I fully see a ‘o’ to demonstrate me typing in the string “root” with key presses and key releases.

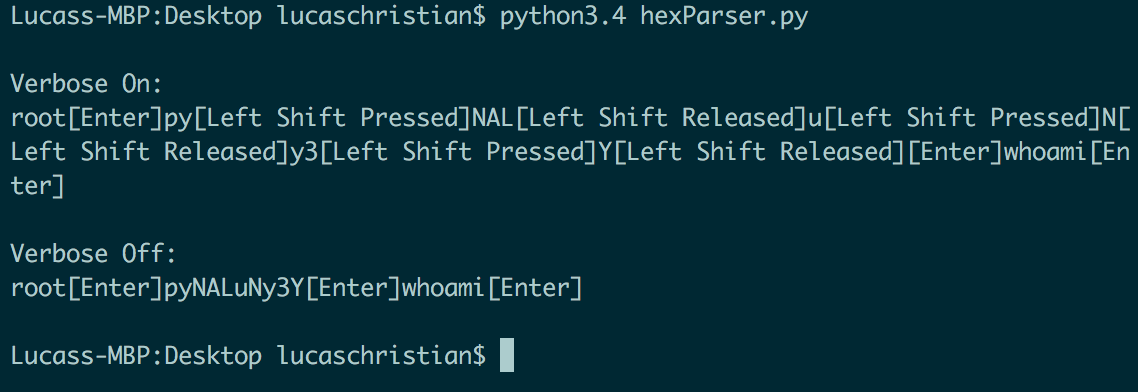

I write a simple script that reads hex that has been exported from the packet capture and decodes all the hex characters that have been transmitted over the wire.

It becomes evident that even though encryption is enabled for the RFB connection, the entire payload is not encrypted. This can be used by an attacker to see each key a Cloud at Cost user presses during the VNC connection.

Conclusion

I have demonstrated that an unsophisticated attacker can not only enumerate and access VNC sessions but also capture all user input sent to the server. I believe it is in the best interest of Cloud at Cost to remediate these vulnerabilities as they undermine the security of their product. Without a mitigation deployed, most security measure thought to be employed can be circumvented as explained. This could result in customer’s virtual machines being compromised or customers losing faith in the product altogether. I have contacted Cloud at Cost on three separate occasions and am awaiting a response.